The Unearthing – “Wait, Jim Henson Made WHAT Now?”

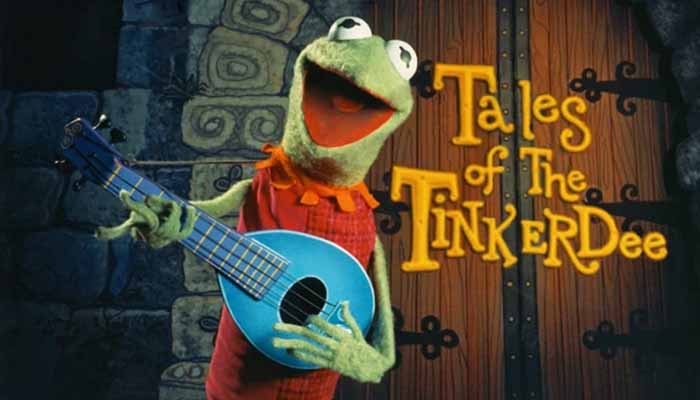

Before the world knew Kermit as a chart-topping, banjo-strumming frog, and long before Miss Piggy was delivering her signature karate chops, there existed a curious, almost mythical television pilot: Tales of the Tinkerdee. This isn’t some forgotten B-side; this is a genuine piece of Jim Henson history, a 1962 unaired pilot that offers a fascinating, and often funny, glimpse into the nascent stages of a creative empire. The very fact that it was “unaired” lends it an air of mystery, a sort of “Lost Ark” of puppetry, making it a coveted find for dedicated Henson aficionados. For years, its existence was more legend than accessible media, with one fan recounting the thrill of acquiring a 16mm film print from an untrustworthy dealer, only later realizing its true rarity. The Paley Center for Media even highlighted it as one of the “rarest of all Muppet projects,” further cementing its enigmatic status.

To truly appreciate Tales of the Tinkerdee, one must journey back to the television landscape of 1962. Jim Henson, already having found success with the five-minute show Sam and Friends, was, along with his key collaborator Jerry Juhl, actively seeking to develop a more substantial, long-form program. Tales of the Tinkerdee was precisely that ambitious shot, an attempt to carve out a larger space in the burgeoning world of television entertainment. The pilot emerged from a relationship Henson had established with the Protestant Radio and Television Center (PRTC) in Atlanta, initially for a different, ultimately unsuitable project about traffic safety featuring a villainous monster named Sneegle who, unfortunately for the project’s moral aims, proved far more popular than the well-behaved protagonists.

The unaired status of Tales of the Tinkerdee is not merely a footnote in its production history; it’s a rich source of speculative amusement. Why did this pilot, into which Henson and Juhl poured their creative energies, fail to secure a broadcast slot?. One can only imagine the expressions on the faces of 1960s network executives as they were presented with a show featuring a lute-playing proto-Kermit spouting what Jerry Juhl himself later described as “god-awful puns and hideous rhymes”. Perhaps the “potato-shaped” witch or an ogre ingeniously (and economically) portrayed by Jim Henson’s own arms and legs proved a bridge too far for the mainstream sensibilities of the era. This “almost-was” quality transforms the pilot from a simple piece of juvenilia into an entertainment artifact that invites playful conjecture.

Adding to its unique historical texture is the fact that while Tales of the Tinkerdee was videotaped in color, the only version known to have survived is a black-and-white kinescope recording. This technical limitation inadvertently bestows upon it an almost “art house” film quality, a grainy, monochrome window into a Technicolor dream. The juxtaposition of this somewhat serious, archival presentation with the inherently whimsical and goofy content – puppets engaging in fairy tale antics – only amplifies its peculiar charm. It is, in essence, a vibrant, colorful concept filtered through the desaturated lens of early television preservation methods, making it a visually distinct piece of Henson’s early portfolio.

Welcome to Tinkerdee – A Land Before Time (Warner Brothers)

The realm of Tinkerdee itself was conceived as a unique fairy tale kingdom. Unlike many later Muppet productions that would directly parody well-known stories, Tales of the Tinkerdee presented an entirely original narrative, though it liberally borrowed and playfully tweaked familiar elements from the broader fairy tale tradition. This approach marked it as a significant early foray into what would become a hallmark of Henson’s style: the fractured fairy tale. The project also served as an outlet for ideas Henson had previously sketched out for a Hansel and Gretel production that never came to fruition, allowing him to finally explore some of those concepts within this new framework.

At the creative helm were Jim Henson and Jerry Juhl, a partnership that would define Muppet productions for decades. Their shared ambition for a “complex puppet production” was beginning to solidify with Tinkerdee, laying crucial groundwork for their future collaborative successes. Henson’s lifelong fascination with fairy tales and folklore was a driving force behind this venture. While some of his later fairy tale adaptations, like The Storyteller, would explore darker and more nuanced themes , Tales of the Tinkerdee leaned into a lighter, more overtly comedic interpretation, already showcasing that distinctive Muppet blend of sincerity and playful subversion.

The decision to craft an original story within the fairy tale genre, rather than simply riffing on an existing classic like Hey Cinderella! , reveals an early ambition that extended beyond mere parody. While the language and tropes of fairy tales provided a familiar scaffolding, Henson and Juhl were already demonstrating a desire to build unique worlds and narratives from the ground up. This impulse towards original world-building can be seen as a nascent precursor to the entirely self-contained universes of later Henson creations such as Fraggle Rock or The Dark Crystal. Tinkerdee was not just playing with the toys in the fairy tale sandbox; it was trying to sculpt its own.

Furthermore, the afterlife of its creative components suggests that Tales of the Tinkerdee functioned as more than just a one-off pilot attempt; it was a vibrant sketchbook of ideas. The fact that characters and the Tinkerdee setting itself were subsequently utilized in sketches for The Today Show (notably “The Rulers of Tinkerdee” on March 8, 1963) , and that its principal puppet characters would reappear in the later Tales From Muppetland television specials , indicates that Henson viewed the pilot not as a failure, but as a successful incubator. No element was truly wasted; instead, the pilot served as a creative wellspring, its parts deemed valuable enough for refinement and redeployment in future projects. This iterative process, where ideas are tested, adapted, and carried forward, would become a consistent feature of Henson’s innovative approach to production.

Meet the Proto-Muppets – A Rogues’ Gallery of Glorious Goofballs

The inhabitants of Tinkerdee were a motley crew, each character a quirky testament to Henson’s burgeoning puppet-building and character-development skills. Their designs and personalities offer a delightful preview of the Muppet mayhem to come.

Tinkerdee’s Most Wanted (and Wonderfully Weird) Residents

| Character Name | Mugshot (Quirky Description) | Known Accomplices (Performed By) | Future Muppet DNA (Connections/Foreshadowing) | Why We’re Still Snickering (Comedic Gold) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kermit | Medieval court minstrel narrator; NOT YET A FROG; sported an orange, “tightly-cropped” fringed collar (not even attached!) ; played a lute. | Jim Henson | First appearance of a collar, a crucial step to his iconic look ; mischievous personality ; voice closer to later Kermit. | The sheer un-frogginess! The detachable collar! The “god-awful puns and hideous rhymes”. He was less “Rainbow Connection,” more “Ye Olde Comedy Open Mic.” |

| Taminella Grinderfall | “Potato-shaped” witch; “witchiest witch of them all” ; considered Henson’s “best character yet” at the time. | Jerry Juhl | Reappeared in Tales From Muppetland specials ; her witty, non-babyish humor set a tone for smart Muppet villains. | A villain carved from a root vegetable! The fact that Juhl, the co-writer, embodied this sassy sorceress adds a layer of meta-hilarity. |

| King Goshposh | “Bumbling” king ; defined by his “perpetually-smoking cigar”. | Jim Henson | Reappeared in Tales From Muppetland and Hey Cinderella! ; evolved into King Rupert in The Frog Prince. | A monarch whose primary policy seemed to be maintaining a lit cigar. His regal pronouncements must have come with a smoke signal. |

| Charlie the Ogre | Dim-witted ogre ; uniquely portrayed by Jim Henson’s own arms and legs, as no other human actors were on screen. | Jim Henson (voice and limbs!) | Precursor to other full-bodied Muppet monsters; his “classic” scenes with Taminella highlighted early character dynamics. | The ultimate in low-budget special effects! Henson literally throwing himself into the role, one limb at a time. The original “man behind the curtain” was the monster. |

| Princess Gwendolinda | The “lovely” princess whose birthday party is the story’s central event. | Archetypal princess figure, a common trope in Henson’s fairy tale explorations. | Her defining characteristic: having a birthday. A truly relatable monarch for anyone who has also experienced an annual aging process. | |

| Prime Minister | Resembled a “proto-Scooter, with curly hair and glasses for eyes”. | An early example of a Muppet with glasses, foreshadowing characters like Scooter or Dr. Bunsen Honeydew. | The “glasses for eyes” is a wonderfully literal puppet design choice. Did he see the world through a spectacle-ularly unique lens? |

Kermit’s appearance in Tales of the Tinkerdee is particularly noteworthy. He was not yet the frog the world would come to adore but rather a “medieval court minstrel narrator”. His most striking visual feature was an orange, “tightly-cropped” fringed collar – a far cry from his later iconic green one – which, amusingly, wasn’t even physically attached to him. This early collar, however, is seen as a pivotal design element, as it “certainly enhances his frogginess and likely caused something to click in Jim’s mind, eventually inspiring him to put that finishing touch on his green alter ego”. It was an accidental step towards an iconic look, a visual experiment that, while not quite right, pointed the way forward. He strummed a lute, not a banjo, and his voice, while losing some of the Southern drawl from his Sam and Friends days, characterized a more “mischievous” personality, often contributing to the on-screen chaos rather than resolving it.

Taminella Grinderfall, the “potato-shaped” sorceress, was reportedly considered by Jim Henson at the time to be the Muppets’ “best character yet”. This preference for Taminella, performed with witty flair by co-writer Jerry Juhl , over the more straightforward Kermit or the “cigar-chomping” King Goshposh, suggests an early appreciation on Henson’s part for characters with strong, quirky, and perhaps more overtly performative personalities. Villains often provide ample opportunity for broader comedic and dramatic expression, and Taminella, with her “witchiest witch of them all” persona, certainly fit that bill.

Then there was Charlie the Ogre, a marvel of resourcefulness. Described as “dim-witted,” Charlie was brought to life by Jim Henson’s own arms and legs, a necessity given the absence of other human performers on screen. This embodiment of “the show must go on (with whatever limbs are available)” is a testament to the playful, hands-on, and often budget-conscious approach that characterized early Henson productions. It was a literal interpretation of giving one’s all to a role and a prime example of the physical comedy and puppetry innovation, sometimes born of sheer necessity, that would become a core component of the Muppet charm.

The Plot Thickens (Like Gravy Left Out Too Long): A Birthday Bash Gone Bonkers

The narrative driving Tales of the Tinkerdee was, in true fairy tale fashion, deceptively simple yet ripe for comedic exploitation. The central conflict revolved around Princess Gwendolinda’s birthday party, an event of great importance in the kingdom, which the nefarious Taminella Grinderfall plots to crash with the singular, dastardly aim of pilfering all the presents. Forget grand political intrigue or epic quests; this was a heist targeting birthday cake and newly acquired toys.

Taminella’s scheme to achieve this present-pilfering goal was a masterstroke of absurdity. She devises a plan to disguise herself as Santa Claus – a bold choice given the story unfolds in the middle of spring – with the dim-witted Charlie the Ogre roped in to serve as her “trusty reindeer, Tonto”. This ludicrous plan, with its seasonal incongruity and questionable choice of reindeer stand-in, provided a perfect vehicle for Taminella’s particular brand of witty villainy and Charlie’s bumbling assistance. The simplicity of this plot – a witch attempting to steal birthday gifts – served a crucial function. It provided a very loose, almost elementary framework that allowed the character-based comedy to take center stage. The narrative wasn’t intended to be the main attraction; the puppets and their antics were. This approach, where a straightforward plot acts as a launchpad for character humor, would become a foundational principle in much of Muppet storytelling.

Guiding the audience through this charming chaos was Kermit, in his role as the minstrel narrator. Armed with his lute, he delivered the story in song, weaving “quatrains with god-awful puns and hideous rhymes,” all set to “very sweet, lilting music”. Kermit wasn’t merely a passive observer; his personality in this pilot was noted as being “more mischievous, contributing to the chaos rather than defusing it” , making him an active participant in the lighthearted pandemonium.

Adding another layer of comedic texture were the anachronisms peppered throughout the script. For instance, Kermit, in his opening song, advises the 1960s audience to “Toucheth not that dial,” while Taminella, in a moment of frustration, might exclaim that she’s “not just whistling Greensleeves!”. These playful winks to the contemporary audience, embedded within a medieval fairy tale setting, are early indicators of the Muppets’ signature meta-humor and self-aware style. By breaking the fourth wall, however subtly, and playing with the conventions of the medium, Henson and Juhl were inviting the audience to be in on the joke, establishing a conspiratorial relationship that would later be a hallmark of productions like The Muppet Show.

Why It’s So Charmingly Clunky (And Why We Love It For That)

Part of the undeniable charm of Tales of the Tinkerdee lies in its wonderfully dated production qualities, which offer a window into the realities of early 1960s television. The most visually striking aspect for modern viewers is the surviving black-and-white kinescope of a program originally videotaped in color. This technical limitation immediately transports the viewer to a different era of media consumption. The kinescope itself, a film recording of a television monitor, physically embodies the ephemeral nature of early television and the methods used for its preservation, making the act of watching it feel like a genuine form of time travel.

User reviews and production notes acknowledge that Tales of the Tinkerdee exhibited a “lower production value” when compared to the more polished Henson works that would follow. This is, perhaps, an understatement. The sets were likely modest, and the special effects, beyond the ingenious use of Henson’s own limbs for Charlie the Ogre , were probably minimal. However, this “makeshift aesthetic,” as one analysis of Muppet productions describes it, is not necessarily a detriment. In the Muppet universe, “what matters… isn’t perfection, but expression”. This philosophy is clearly evident even in this very early work. The visible seams, the less-than-slick presentation, contribute to a unique sense of authenticity and allow the inherent creativity and personality of the puppets and performers to shine through more directly. It’s an early example of resourcefulness breeding a distinct and endearing style.

The auditory experience was similarly a product of its time, with a mono sound mix. Kermit’s musical contributions, while narratively crucial, were sometimes noted as being “a little flat” , a charming reminder of a pre-Auto-Tune era. And then there were the puns. Jerry Juhl’s candid description of Kermit’s narration featuring “god-awful puns and hideous rhymes” is a comedic gift in itself. One can only imagine the groan-inducing wordplay that filled the airwaves of the PRTC studio in Atlanta – perhaps the princess was “royally” miffed, or the king found the situation “crowningly” complex. These linguistic antics, so bad they veer into good, are a key component of its quirky appeal.

Tinkerdee’s Fingerprints All Over Future Muppet Magic

Despite its failure to secure a network broadcast, Tales of the Tinkerdee was far from a creative dead end. Instead, it served as a crucial incubator, planting numerous seeds that would blossom in subsequent, highly successful Muppet productions. Its influence can be traced in character development, thematic explorations, and even the iterative approach to puppet design.

Several key characters introduced in Tinkerdee proved too compelling to be left in the pilot’s obscurity. Kermit, Taminella Grinderfall, and King Goshposh all reappeared in the Tales From Muppetland television specials that followed a few years later, such as The Frog Prince and Hey, Cinderella!. King Goshposh, for example, also graced the court in Hey Cinderella! and was later refined into the character of King Rupert II for The Frog Prince. This demonstrates that the pilot, even if “failed” in terms of immediate broadcast, was a successful testing ground for characters with lasting appeal. Kermit’s rudimentary collar in Tinkerdee was a visual stepping stone towards his globally recognized pointed green collar, a small but significant evolutionary detail.

Thematically, Tinkerdee solidified Henson’s interest in the “fractured fairy tale” format. While later specials would often directly satirize specific tales, Tinkerdee‘s original story, which merely borrowed and reconfigured fairy tale tropes, showcased an early commitment to this playful deconstruction of classic narratives. The characteristic Muppet blend of “gentle sincerity with clever fairy tale twists and humor” was already palpable in this 1962 production. This early experiment also contributed to the development of a “Muppet family” dynamic, with recurring characters creating a sense of a shared universe, a concept that would become central to the appeal of The Muppet Show and other ensemble pieces. The reuse of puppets like King Goshposh and Taminella across different stories suggests the nascent formation of a Muppet “repertory company,” where versatile puppet performers could inhabit various roles, fostering audience familiarity and a sense of continuity within Henson’s fairy tale world.

The perceived “failure” of Tinkerdee to air was, in retrospect, a catalyst for refinement. Henson and his team were able to identify the strongest elements from the pilot – its engaging characters, its unique comedic voice, its playful approach to genre – and redeploy them more effectively in later, successful ventures. This iterative design process, where ideas are tested, lessons are learned, and components are recycled and improved, is a hallmark of sustained creative innovation. Tales of the Tinkerdee was not a misstep but a vital part of that ongoing creative journey.

So, Should You Hunt Down This Fuzzy Fossil?

For enthusiasts of Jim Henson’s work, early television history, or simply wonderfully quirky pop culture artifacts, Tales of the Tinkerdee is more than just a historical footnote; it’s a delightful and illuminating discovery. It offers a hilarious and fascinating glimpse into the primordial soup from which the Muppets emerged, showcasing raw, unpolished Henson genius in its nascent stages. The pilot is a testament to the “make it work” spirit that defined his early career, where resourcefulness and creativity triumphed over budgetary constraints.

The humor, described by at least one viewer as “witty rather than babyish” even by today’s standards, still resonates. For the die-hard Henson devotee, it is considered “essential” viewing, a charming piece that rewards even those who approach it with modest expectations. Despite not being picked up for a series, the pilot was undeniably a “charmer” , a half-hour of inventive puppetry and gentle comedy.

Ultimately, Tales of the Tinkerdee stands as a reminder that even creative giants have early drafts, and sometimes those drafts involve potato-shaped witches, cigar-puffing kings, and ogres ingeniously constructed from the puppeteer’s own limbs. It showcases a playful persistence, a willingness to experiment and learn, even when initial efforts don’t achieve immediate mainstream success. Henson and his team didn’t abandon the concepts or characters from Tinkerdee; they tinkered, refined, and carried forward the most valuable pieces into future triumphs.

The enduring appeal of this fuzzy fossil lies in its authenticity. It captures a moment of pure creative exploration, unburdened by the weight of global fame or established character expectations. It’s the infectious energy of “let’s put on a show,” preserved in grainy black and white. So, the next time Kermit the Frog is seen conducting an orchestra or interviewing a major celebrity, it’s worth taking a moment to remember his humble, lute-strumming, pun-slinging origins in the whimsical land of Tinkerdee. The journey from that unaired pilot to international icon is a testament to the enduring power of a good idea, a lot of felt, and an unwavering belief in the magic of puppetry.