A Shard of Vision in a World of Felt

In the landscape of 1980s cinema, already burgeoning with imaginative leaps in science fiction and fantasy, Jim Henson’s The Dark Crystal (1982) stands as a singular, audacious achievement. Emerging from the mind best known for the beloved, brightly colored chaos of The Muppets, this film was a startling departure: a dark, mythic fantasy epic populated entirely by puppets, devoid of human actors, and steeped in complex spiritual and philosophical themes. It was a project born from a deep-seated artistic ambition, pushing the boundaries of puppetry and practical effects to realize a world unlike any seen before. This report delves into the creation of The Dark Crystal, exploring its conceptual origins, the pivotal collaboration between Jim Henson and designer Brian Froud, the groundbreaking technical innovations employed, the crafting of its unique narrative and themes, the challenges of its production, its initially misunderstood reception, and its eventual ascent to become a cherished cult classic and a cornerstone of the Jim Henson Company’s legacy.

The Spark of Mithra: Conceptual Origins

The genesis of The Dark Crystal wasn’t a single bolt of inspiration but rather a confluence of visual stimuli, creative restlessness, and deeply held philosophical interests. One often-cited catalyst occurred when Henson encountered a lavish illustration by Leonard Lubin in a 1975 edition of Lewis Carroll’s “The Pig-Tale”. The image depicted two elegantly dressed crocodiles lounging in a sophisticated Victorian bathroom. Henson was captivated by “the juxtaposition of this reptilian thing in this fine atmosphere,” sparking ideas about corrupt, aristocratic reptilian creatures ruling a decadent society. This initial visual spark led Henson to draft a treatment for a film titled Mithra, which contained nascent elements of the final story, including the core idea of warring factions that had split from a single, original species, though the exact mechanism (later the Crystal) was still unclear.

Further conceptual grounding came from Henson’s earlier, less successful foray into darker puppetry with “The Land of Gorch” segments for the first season of Saturday Night Live in 1975. Though unpopular with the SNL cast and crew, the experience solidified Henson’s desire to create a fully realized fantasy world “with as much depth and texture as ours and with as much history behind it”. This ambition went beyond mere entertainment; Henson held a conviction that challenging children, even frightening them, was essential for growth. He aimed to return to the darker, more primal roots of fairy tales, citing the Brothers Grimm as an influence, believing it wasn’t “healthy for children to always feel safe”.

This artistic drive intertwined with Henson’s personal spiritual explorations. Described as a “spiritual searcher,” Henson drew from a blend of theosophy, Hinduism, Taoism, and New Age philosophies. He was particularly influenced by Jane Roberts’s controversial book Seth Speaks, which detailed channeled messages from a multidimensional entity. Henson insisted screenwriter David Odell read the book before working on the script, seeing it as a way to explore different realities. The film’s central concept of the urSkeks splitting into the benevolent Mystics and the malevolent Skeksis, destined to reunite, is widely seen as Henson’s creative response to the ideas presented in Seth Speaks. This fusion of a striking visual concept (reptilian aristocrats), a desire for immersive world-building (post-Gorch), a belief in challenging storytelling (dark fairy tales), and deep philosophical underpinnings (spirituality, Seth Speaks) formed the multifaceted foundation upon which The Dark Crystal would be built.

Forging Thra: The Henson-Froud Collaboration

While Henson provided the initial conceptual sparks and philosophical drive, the unique visual identity of The Dark Crystal owes its existence to the pivotal collaboration with English fantasy artist Brian Froud. In 1977, Henson encountered Froud’s work, particularly the book The Land of Froud and illustrations in Once Upon a Time, and was immediately captivated. Froud’s intricate, ethereal, and slightly unsettling style, steeped in folklore and nature, resonated perfectly with Henson’s vision for a darker, more organic fantasy world. Henson saw the “wonderful challenge” of translating Froud’s two-dimensional designs into three-dimensional, performing characters.

Excited by this potential, Henson largely set aside his Mithra concept to build a new world from the ground up with Froud. Henson arranged to meet Froud in London, a meeting followed by a visit to Froud’s home in Chagford, Dartmoor, Devon, accompanied by Henson’s daughter, Cheryl. The mystical, contrasting landscape of Dartmoor – windswept moors, lush streams, ancient stones – deeply impressed Henson and became a key inspiration for the film’s environments, reinforcing the organic, lived-in feel Froud’s art suggested. Henson embraced Froud’s belief that “rocks lived and plants walked,” blurring the lines between animal, mineral, and vegetable.

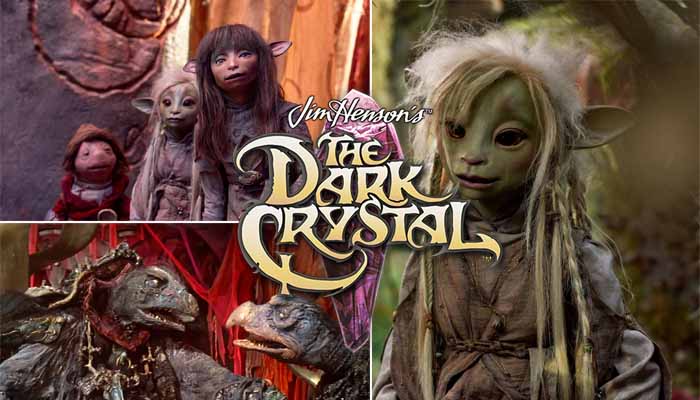

Froud was appointed the film’s conceptual and costume designer, tasked with visualizing the entire world of Thra – its landscapes, its flora and fauna, and crucially, its inhabitants. Henson’s typical approach involved extensive world-building before finalizing a script, allowing Froud’s designs to guide the narrative’s emergence. Froud began sketching, developing the distinct looks of the key races: the gentle, wizened Mystics (urRu) and the grotesque, decaying Skeksis, whom Froud described as “part reptile, part predatory bird, part dragon,” adorned in decaying finery inspired by the original crocodile illustrations. The elf-like Gelflings also underwent significant evolution, initially appearing more animalistic with blue fur before being refined to a more relatable, humanoid form. This collaborative process, where Froud’s art served as the visual genesis and Henson’s team worked to realize it physically and dramatically, defined the film’s creation. It wasn’t merely illustration; Froud’s concepts were the bedrock upon which the entire project was constructed. The synergy was palpable: Froud provided the soul and look of Thra, while Henson provided the pathway to bring it to life.

Masters of Puppetry: Innovation in Motion

The Dark Crystal represented a monumental leap forward in the art and technology of puppetry and animatronics. Marketed as the first live-action film with no human actors on screen, it demanded the creation of the most complex and nuanced puppets ever attempted at the time. Henson’s goal was ambitious: to achieve a level of realism where viewers would forget they were watching puppets and accept the inhabitants of Thra as living creatures within their own world. This required pushing the boundaries of existing techniques and inventing new solutions.

The Henson Creature Shop, under the supervision of figures like Sherry Amott, assembled a large team of sculptors, fabricators, and engineers. They employed a diverse array of techniques: traditional hand-and-rod puppetry, intricate cable-controlled mechanisms running under flexible foam latex skins, performers fully encased in creature suits, and even marionettes. Foam latex, chosen for its ability to capture fine detail and its relatively light weight compared to silicone, was crucial for the creatures’ skins. Innovations in radio control (RC) technology, refined by specialists like Faz Fazakas, proved vital, particularly for the Gelfling protagonists, Jen and Kira. RC servos allowed for subtle, remote-controlled facial expressions (eyes, eyelids, ears), freeing the primary puppeteers (Henson for Jen, Kathryn Mullen for Kira) to focus on the broader physical performance and acting, unencumbered by excessive cables. This contrasted sharply with the Skeksis, who often required a “swarm” of assistants operating cables for their elaborate facial movements.

The complexity of the puppets necessitated multiple performers working in concert. Some characters, like the Gelflings and Skeksis, could require up to four or five puppeteers simultaneously – one primary performer for the body and main voice/mouth movements, and assistants operating limbs, facial features via cable or RC, or even providing additional support. The physical demands placed on the performers were often extreme, blending artistry with sheer athleticism. Operating the Skeksis involved performers hidden inside heavy, elaborate costumes, often working on raised sets with sections of the floor removed to accommodate them. The performers needed strength, stamina, and incredible coordination, monitoring multiple camera feeds while delivering lines and manipulating the complex mechanisms.

Perhaps the most physically taxing performance was required for the Mystics. To achieve their slow, deliberate, hunched-over movement, puppeteers had to crawl, contorting their bodies into a ball while holding one hand up to operate the head and neck, often bearing significant weight. Operating the Mystics’ four arms required additional puppeteers working in close proximity. Even Jim Henson, a veteran puppeteer, reportedly found the Mystic posture incredibly difficult to maintain for more than a few seconds. Similarly, the performers inside the heavy, cumbersome Garthim suits required specially constructed slings to rest between takes. To ensure convincing movement, many puppeteers received training in mime and modern dance.

The experience gained by Henson, Frank Oz, and others while creating Yoda for The Empire Strikes Back (1980) served as a crucial proving ground. Working with George Lucas provided invaluable lessons in complex creature performance and “tech transfer,” directly informing the approaches used for The Dark Crystal‘s even more ambitious cast. Henson constantly emphasized the performer’s role, iterating on designs, disassembling and rebuilding puppets until the performance felt right, ensuring the technology served the character, not the other way around.

The following table summarizes the puppetry approaches for some key inhabitants of Thra:

| Character/Species | Brief Description | Key Puppeteering Technique/Challenge | Relevant Snippet Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gelflings (Jen, Kira) | Elf-like protagonists | Hand/rod operation; RC heads (Kira) for subtle expression; multiple puppeteers; lightweight construction prioritized | |

| Skeksis | Vulture/reptile villains, decaying aristocracy | Performer inside heavy suit; raised sets; assistants for cables/servos; complex facial mechanics; powerful but frail movements | |

| Mystics (urRu) | Gentle, four-armed wizards, ancient and slow | Extreme physical performance (crawling, contorted posture); weight-bearing; multiple puppeteers for arms; meditative movement | |

| Aughra | One-eyed astronomer/sorceress | Complex head (RC/servo + hand control); support backpack for head weight; performer’s gloved hands for Aughra’s hands | |

| Podlings | Small, potato-like villagers | Hand puppets; expressive, simple faces; focus on group interactions | |

| Fizzgig | Kira’s furry, aggressive pet | Hand puppet; complex mouth mechanism with multiple rows of teeth; energetic, erratic movement | |

| Landstriders | Tall, swift, stilt-walking mounts | Performers on stilts requiring balance and coordination; safety wires used; creating sense of speed and agility | |

| Garthim | Crab-like soldiers, Skeksis enforcers | Heavy, cumbersome suits requiring performers inside; limited visibility; creating menacing, clanking movement; required rest slings |

This intense period of innovation cemented the Henson Creature Shop’s reputation as a leader in character creation, demonstrating that puppetry could achieve unprecedented levels of realism and dramatic depth on screen.

Lore of the Crystal: Crafting the Narrative and Themes

Unlike productions driven primarily by script, the narrative of The Dark Crystal grew organically from the established visual world and Henson’s thematic preoccupations. An early 25-page story outline, titled “The Crystal,” was drafted by Henson and his daughter Cheryl during a snowstorm-induced delay in New York in 1978. This early version already focused on the core concept of the split between the Mystics and the Skeksis, the divided nature of a single ruling species. Screenwriter David Odell was later brought on board to develop the full screenplay, working closely with Henson and Froud.

The resulting story is steeped in a rich, invented mythology. Central to this lore is the Crystal of Truth, a powerful entity whose cracking a thousand years prior during a “Great Conjunction” of Thra’s three suns led to the sundering of the god-like urSkeks. This cataclysm split the urSkeks into two distinct races embodying their divided nature: the gentle, passive, wise Mystics (urRu) and the cruel, aggressive, materialistic Skeksis. The Skeksis seized control, ruling Thra with an iron fist and exploiting the Crystal’s power, now darkened, to unnaturally extend their own lives by draining the vital essence of other creatures, primarily the peaceful Podlings. The narrative follows Jen, believed to be the last of the Gelfling race (nearly exterminated by the Skeksis), who is tasked by his dying Mystic master to fulfill a prophecy: find the lost shard of the Crystal and heal it before the next Great Conjunction, thereby restoring balance and potentially reuniting the two sundered races.

A fascinating aspect of the early development involved language. Initially, Henson envisioned the Skeksis speaking their own guttural, alien language, with the audience inferring meaning through performance and context. Alan Garner and later David Odell developed constructed languages, drawing inspiration from ancient Egyptian, Greek, and Indo-European roots, creating distinct dialects for the Skeksis and Mystics to reflect their shared origin and subsequent divergence. However, test screenings revealed that audiences, particularly younger viewers, found the extensive non-English dialogue confusing and alienating. Consequently, Henson and Odell painstakingly rewrote and re-recorded the Skeksis dialogue in English, carefully matching the new lines to the existing puppet lip-flaps. This pragmatic decision, while perhaps sacrificing some artistic purity, ensured broader accessibility. Interestingly, Odell felt the process resulted in a strangely stilted, alien quality to the English dialogue that might not have been achieved otherwise. While the Skeksis language was largely abandoned for the film, the concept of constructed languages within the world of Thra resurfaced decades later with the creation of a fully developed Podling language by linguist and author J.M. Lee for the prequel series The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance.

Beyond the plot mechanics, The Dark Crystal resonates with profound themes. The central duality of the Skeksis and Mystics serves as a powerful metaphor for the divided nature of the self, exploring the tension between materialism and spirituality, aggression and passivity, intellect and intuition. This reflects Henson’s interest in the Seth Speaks material, which explored concepts of consciousness creating reality and the multifaceted nature of the soul. The film champions themes of balance and harmony, suggesting that wholeness requires the integration of these opposing forces, both within individuals and the world. The quest itself is restorative rather than destructive, focused on healing the Crystal, not defeating an enemy in traditional combat. Furthermore, the film carries subtle environmentalist undertones, depicting the Skeksis’ rule as a blight upon the land, causing decay and exploiting natural resources (including other living beings) for their selfish gain. It functions as a critique of unchecked power, greed, and the dangers of societal stratification. These interwoven layers of mythology and thematic depth elevate The Dark Crystal beyond a simple fantasy adventure into a more complex, allegorical work.

Bringing Thra to Life: Production and Design

Realizing the intricate world conceived by Henson and Froud presented significant production challenges. Principal photography took place primarily at Elstree Studios in Borehamwood, Hertfordshire, England, from April to September 1981. The complexity of the puppetry and effects demanded controlled studio environments for most scenes. However, to capture the desired sense of scale and natural wonder, exterior scenes were filmed in evocative real-world locations, including the dramatic landscapes of the Scottish Highlands, the unique limestone formations of Gordale Scar in North Yorkshire, and woodlands near Twycross, Leicestershire.

The set design was a crucial element, translating Froud’s conceptual art into tangible environments. Production designer Harry Lange worked to create alien yet believable landscapes, from the cluttered, mystical observatory of Aughra (whose Orrery was later recreated digitally for Age of Resistance ) to the decaying gothic grandeur of the Skeksis’ Castle of the Crystal and the serene, organic Mystic Valley. Froud remained deeply involved, ensuring the sets reflected the overall aesthetic, drawing inspiration from the Dartmoor landscape with its sense of ancient energy and living nature. Cinematographer Oswald Morris, a veteran known for his work on musicals like Oliver!, faced the challenge of lighting Froud’s designs. Froud’s painterly style, when directly translated using Morris’s preferred Lightflex system (a front-projection method for controlling light and contrast), initially appeared too flat on film. Adjustments were made, dialing back the system and tweaking costume and set colors “in camera” to achieve the desired Froudian look with sufficient depth. The production also utilized traditional practical effects techniques like miniatures for establishing shots, detailed painted backdrops to extend sets, and blue screen compositing for certain sequences.

The entire endeavor was ambitious and costly. While precise figures vary, the budget is generally cited in the range of $15 million to $26 million – a significant sum for a puppet film in the early 1980s. The intricate puppetry, bespoke creature fabrication, detailed sets, and extended development period contributed to the high cost and lengthy production schedule. The technical complexity added roughly 25% more time to the shooting schedule compared to a conventional live-action film. Throughout the process, Henson faced skepticism from financial backers and studio executives, who struggled to grasp the film’s unique concept and market potential, leading to the project being bought and sold several times. Henson ultimately had to personally fund aspects of the marketing to ensure the film received a proper release. These production hurdles underscore the immense creative and financial risks involved in bringing such an unconventional vision to the screen.

Another World, Another Reaction: Initial Reception

Upon its release on December 17, 1982, The Dark Crystal met with a decidedly mixed reception from critics and audiences, failing to immediately capture the widespread adoration associated with Jim Henson’s Muppet creations. Mainstream critics were divided. While many praised the film’s stunning visual artistry, groundbreaking puppetry, and technical achievements , others found fault with its narrative and tone. Vincent Canby of The New York Times dismissed it as “watered down J.R.R. Tolkien” and lacking charm , while Dave Kehr of the Chicago Reader found it lifeless. Rex Reed in the New York Post criticized the budget and found the characters unappealing. Some reviews, however, were positive; Variety lauded it as a “dazzling technological and artistic achievement” that could teach morality , and Bill Cosford of the Miami Herald noted adults were “transfixed” by its realistic fantasy. Siskel and Ebert reviewed the film, though the available snippets only confirm the review’s existence, not its specific content.

Audiences, particularly those expecting the lighthearted humor of The Muppets, were often baffled or even disturbed by the film’s darker, more serious tone and complex mythology. Many parents felt the film was too frightening for young children, citing the menacing Skeksis, the unsettling concept of essence-draining, and moments of violence. This departure from Henson’s established brand created a significant dissonance, hindering its immediate appeal.

Commercially, The Dark Crystal performed respectably but was not the blockbuster hit some might have hoped for given Henson’s name and the film’s budget. It opened third at the North American box office, eventually grossing between $40 million and $44 million worldwide against its estimated $15-26 million budget. While it turned a profit, this return was considered a disappointment by industry standards, especially given the production costs and Henson’s previous successes. It finished as the 16th highest-grossing film domestically in 1982, overshadowed by behemoths like E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (released the same year).

The film’s initial lukewarm reception can be understood not just through its own perceived shortcomings, but also as a consequence of being Henson’s first major foray into dark fantasy. It broke audience expectations associated with his name. The subsequent commercial failure of Labyrinth in 1986, despite incorporating more conventional elements like human actors (David Bowie), musical numbers, and increased humor, suggests that the market in the 1980s may simply not have been receptive to Henson occupying this particular creative space. The Dark Crystal, being the first to challenge these expectations, faced the most significant uphill battle against audience preconceptions and critical bewilderment.

The Crystal Shines Bright: Legacy and Cultural Resonance

Despite its initially muted reception, The Dark Crystal proved remarkably resilient. Over the ensuing decades, the film steadily cultivated a passionate cult following, finding its audience through repeated viewings on home video formats like VHS, DVD, and Blu-ray. Away from the pressures of opening weekend box office and initial critical assessments, viewers could immerse themselves in the film’s unique world and appreciate its artistry on their own terms. This led to a significant re-evaluation, with the film now widely regarded by many critics and fans as a masterpiece of fantasy cinema and a crowning achievement for Henson.

Its influence on the fantasy genre and the art of practical effects is undeniable. It demonstrated that puppetry could be utilized for serious, dramatic storytelling in a complex fantasy setting, paving the way for future projects that relied heavily on practical creature effects. Its intricate designs and ambitious world-building have been cited as influences by creators in various fields, from authors like M.B. Weston (The Elysian Chronicles) to potentially game designers (speculation regarding The Legend of Zelda). The film remains a benchmark for practical creature design and execution, showcasing a level of tactile artistry often contrasted with later reliance on CGI.

The world of Thra proved fertile ground for expansion beyond the original film. A wealth of supplementary material has been produced, deepening the lore and continuing the story. This includes Brian Froud’s companion book The World of The Dark Crystal , novelizations , prequel novels exploring Gelfling society by J.M. Lee , children’s books , comprehensive visual histories , and numerous comic book series, including Marvel’s original adaptation, Archaia’s Creation Myths exploring the origins of the urSkeks , and continuations like The Power of The Dark Crystal. Merchandise ranging from board games and RPGs (though some were unreleased) to perfumes and clothing further cemented its place in popular culture. Most significantly, the enduring fascination led to the creation of the ambitious Netflix prequel series, The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance (2019). Directed by Louis Leterrier, the series returned to Thra using primarily practical puppetry, augmented by modern digital effects for enhancements and puppeteer removal. It received widespread critical acclaim, won an Emmy Award for Outstanding Children’s Program, and was praised for its faithfulness to the original’s spirit while expanding the world and characters. Despite its success, Netflix controversially canceled the series after a single season, citing viewership metrics.

The film’s rich thematic tapestry continues to invite analysis and interpretation. Its core ideas of duality, the search for balance, spirituality versus materialism, and the critique of corrupt power structures remain relevant. Scholars and fans explore its meaning through various lenses: mythology theory, seeing it as a modern articulation of ancient archetypes ; psychology, particularly Freud’s concept of the “uncanny” (the familiar made unfamiliar) evoked by the lifelike yet alien puppets ; gender studies, analyzing the matriarchal Gelfling society and potential genderqueer interpretations of characters ; and even post-colonial theory, reading the Skeksis’ oppressive rule over Thra’s native inhabitants as an allegory for historical colonialism and exploitation.

For Jim Henson personally, The Dark Crystal was more than just another project; it was a deeply personal artistic statement. It represented his ambition to push his chosen art form into new territory and to be recognized as a serious filmmaker beyond the confines of the Muppets. While he didn’t live to see the film achieve its widespread acclaim, its eventual success and enduring legacy solidified its importance. Following the sale of The Muppets to Disney in 2004, The Dark Crystal (along with Labyrinth) became a “crown jewel” property for the independent Jim Henson Company, representing the darker, more complex fantasy side of his creative output. The film’s journey from misunderstood risk to beloved classic demonstrates the power of artistic persistence and the ability of unique visions to find their audience over time, often through the evolving landscape of media distribution, particularly the rise of home video which allowed for its crucial reappraisal.

The Enduring Shard of Imagination

The Dark Crystal stands as a remarkable convergence of artistic vision, technical ingenuity, and profound thematic exploration. Born from Jim Henson’s desire to create something entirely new and challenging, it blossomed through the unique synergy with Brian Froud’s evocative artistry, resulting in a fantasy world of unparalleled detail and organic strangeness. The film pushed the boundaries of puppetry and practical effects, demanding innovation at every turn and showcasing the incredible skill and dedication of the Henson Creature Shop team and performers. Its narrative, woven from threads of mythology, spirituality, and a critique of power, offered a depth unusual for mainstream fantasy films of its era.

Its journey was far from easy. Conceptual hurdles, immense production challenges, studio skepticism, and an initial wave of critical and audience misunderstanding marked its difficult birth. The film that aimed to be “another world, another time” was perhaps too alien, too dark, too different for audiences accustomed to Henson’s more familiar creations in 1982.

Yet, the shard of imagination embedded within The Dark Crystal proved enduring. Through the passage of time and the advent of home video, the film found its devoted audience, its artistry was reappraised, and its influence grew. It stands today not merely as a cult classic, but as a testament to Jim Henson’s unwavering artistic vision, his willingness to take creative risks, and the enduring power of handcrafted fantasy. The Dark Crystal remains a singular work, a beautifully realized, deeply personal film whose magic continues to resonate, proving that even cracked and initially misunderstood visions can, in time, be made whole and shine brightly for generations to come.